This performance recording of a 1953 Berlin production is well worth the attention of anyone who is fond of Donizetti's Lucia da Lammermoor. Or in this case, von.

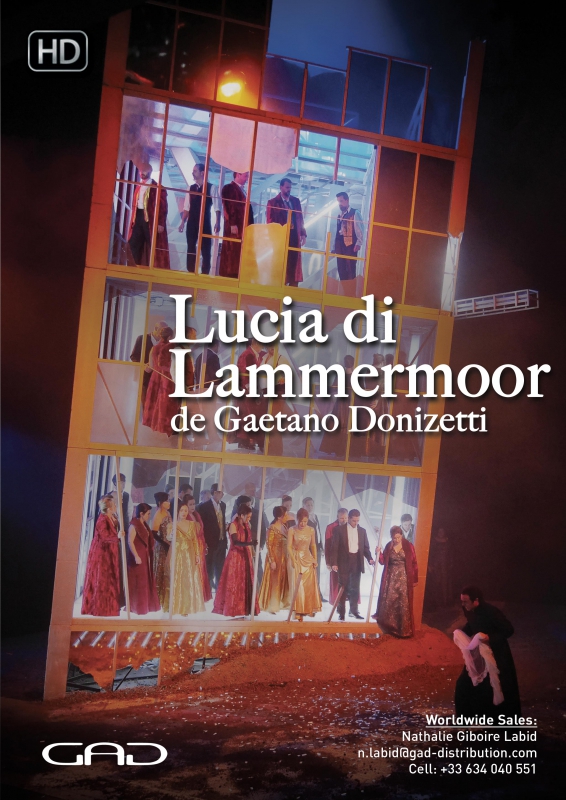

- Donizetti: Lucia di Lammermoor Gaetano Donizetti. 3.3 out of 5 stars 4. Only 1 left in stock - order soon. Lucia Di Lammermoor.

- 'Lucia di Lammermoor' by Gaetano Donizetti libretto (English Italian) Roles Lucia - coloratura soprano Lord Enrico Ashton, Lord of Lammermoor; Lucia's brother - baritone Sir Edgardo di Ravenswood - tenor Lord Arturo Bucklaw, Lucia's bridegroom - tenor Raimondo Bidebent, a Calvinist chaplain - bass.

By Peter Clark

Zillion designs free logo maker free. Donizetti's Lucia di Lammermoor has rarely been out the Metropolitan Opera repertory in the company's 137-year history. With 611 performances to date, Lucia outranks all other Italian bel canto operas in popularity except for Rossini's comedy Il Barbiere di Siviglia, which has been given 632 times.

In the first half-century of Met history, Lucia was the inevitable calling card of the most renowned coloratura sopranos of the day—and it was an era with a steady stream of brilliant virtuoso singers. Marcella Sembrich (pictured above) sang Lucia on the second night of the Met's 1883 opening season, repeating it ten more times to great acclaim. Following a brief period of nine seasons in which a German troupe performed at the Met, Lucia returned in 1892 for a single performance with one of the iconic songbirds of the 19th century, Adelina Patti. The next year, another legendary soprano, Nellie Melba (pictured below), made her Met debut as Lucia, a role which would practically be her personal property for the next decade. Lucia was so closely associated with Melba that she would often add the character's famous mad scene as an encore at performances of other operas she was singing. The first Met performances of La Bohème, in November 1900, featured Melba as Mimì, and once Puccini's tragedy was over, the great soprano, perhaps thinking her audience had not gotten its just desserts, would come out and sing the Lucia mad scene. On tour once in Chicago, when the tenor in Tannhäuser fell ill and couldn't finish the final act, Melba, the evening's Elisabeth, compensated the audience by having a piano wheeled out so she could sing the mad scene.

That Melba was first and foremost a vocal, rather than dramatic, sensation, is evident from a review by W. J. Henderson, one of the eminent critics of the day. 'Mme. Melba was in excellent voice last night, and consequently she was heard to the best advantage. It would be easy enough for a genuine actress to make the rôle of Lucia theatrically effective in spite of the hollowness of the pretty music, but no one ever does act it, and consequently the public has come to accept it as a part in which the unaided exhibition of vocal technics is the whole issue. This is a good attitude for Mme. Melba, for she never acts, even when she thinks she does. But she sings admirably, and last night her work was up to its best mark.'

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-11832756-1523141378-6099.jpeg.jpg)

After Melba's reign as Lucia, Sembrich returned, often with Enrico Caruso as her Edgardo. The tenor hero was often cast with a heavier voice than it is today, with singers like Francesco Tamagno, Verdi's first Otello, and Francesco Vignas and Andreas Dippel, both Wagnerians, taking the part at the Met. One reason may have been that Lucia was often heavily cut, and would sometimes end after the mad scene, eliminating Edgardo's lyrical final scene. As a truncated Lucia made for a rather short evening, the program was sometimes supplemented by a performance of Cavalleria Rusticana or Pagliacci, or some other short piece. Giuseppe Cremonini, one of Melba's partners, sang both Edgardo and Turiddu in Cavalleria in the same evening. Edgardo's final scene was included in Caruso's performances, but it wasn't until Beniamino Gigli sang the role in the 1920s that the part was regularly attributed to a lyric tenor.

In 1911, the phenomenal Italian coloratura Luisa Tetrazzini made her Met debut as Lucia. Her career with the company was short, and she was succeeded in the role by noted sopranos Frieda Hempel in 1913 and Maria Barrientos in 1916. One of the most sensational singers of the century took over the part in 1921: the legendary Italian Amelita Galli-Curci (pictured above). Widely popular in part due to her best-selling records, Galli-Curci was particularly renowned for her remarkably beautiful vocal timbre. Musical America's critic wrote: 'Mme. Galli-Curci's lovely voice was of velvety sheen in the music of the unhappy bride and there was much winsomeness in her picturization of Donizetti's heroine. The ‘Mad Scene' has been sung more brilliantly, but not in recent memory have some of the earlier melodies come to the ear with such suave beauty of tone.'

Though she remained the most prominent Lucia through the 1920s, Galli-Curci sang less well as time went on, probably due to a thyroid goiter that eventually required surgery. In 1924, another Italian, Toti Dal Monte, made her Met debut as Lucia, and although she was highly regarded for the part in her native land, her success in New York was limited.

Then came, in 1931, the soprano who would dominate the role of Lucia for the next 25 years. French soprano Lily Pons (pictured above) was petite, pretty, and had an extraordinary upper register. She regularly interpolated Fs above high C, and even higher notes, into her performances. Though she was less of a virtuoso technician than her predecessors, she had plenty of charm, and audiences loved her. New York Times critic Olin Downes wrote, 'Miss Pons is not, and will not be, a Patti or a Tetrazzini. Her voice has range and freshness when it is heard at its full value, and not marred by faulty breath-support or vibrato. Certain passages yesterday were sung with marked tonal beauty and emotional color. In the ‘mad scene' some of the bravura passages were tossed off with a hint of the virtuoso spirit that this thinly glazed music demands. In other places the singer was not so fortunate.'

Pons's long reign in Lucia at the Met ended with a complete change in how the opera was viewed. Maria Callas (pictured above) sang only six performances of the part at the Met in 1956 and 1958, but her intense acting, musicality, and attention to text made for a powerful theatrical experience. No longer could Lucia be considered a bit of outdated fluff staged to show off the prima donna's virtuosity. The central figure had to be recognized as a tragic heroine of real emotional depth. Henderson's observations about the dramatic possibilities of the role were finally justified.

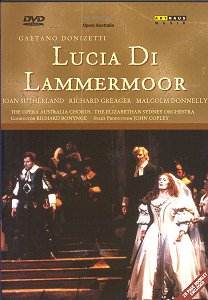

Taking Lucia seriously became the prevailing attitude of singers, conductors, and directors. It showed even when one more brilliant virtuoso, Joan Sutherland (pictured above and at the top of this page), made her Met debut in the part in 1961. Though she was by no means an actress in the mold of Callas, she had carefully worked on her portrayal with director Franco Zeffirelli in London. And not since the days of Melba and Sembrich had New York heard this kind of dazzling vocalism in Lucia. Critic Irving Kolodin said, 'Joan Sutherland came, sang, and conquered the Metropolitan Opera House in her awaited debut as Lucia … this is a voice consistent in timbre through two octaves (E flat to E flat in this part) with scarcely a break—full, ringing, and clear at the top, solid in the middle, viola-mellow at the bottom.'

Twenty years after her Met debut, Sutherland sang Lucia again in the company's first telecast of the opera. Approaching the age of 60, the Australian diva could still astound audiences, and along with the stylistically elegant Edgardo of Alfredo Kraus, the pair provided a glimpse of what gives Lucia di Lammermoor the popular appeal it has always enjoyed at the Met.

Peter Clark is the Met's Director of Archives

The action takes place in Scotland during the nineteenth century.

Act I The Parting

Scene 1 Ravenswood Castle

Enrico Ashton's family fortunes are in jeopardy. Only his sister Lucia can salvage the situation by means of an expedient marriage. Normanno reveals that Lucia is in love with Edgardo, laird of Ravenswood. The Ravenswoods were ousted by the Ashtons and their ancient estate is now in Enrico's possession. Edgardo lives on the edge of the estate in the ruins of a castle and has been seen having secret trysts with Lucia. Enrico vows to end the affair and destroy his enemy.

Scene 2

Accompanied by her companion Alisa, Lucia awaits Edgardo. She conjures up the image of a fountain where a jealous Ravenswood ancestor once killed his lover. She has recently seen the ghost of the murdered young woman, which Alisa interprets as an ill omen for Lucia's love affair with Edgardo. Lucia, however, dismisses her friend's warning.

Edgardo arrives and tells Lucia that he must soon leave for France in order to form an alliance to fight the cause of Scotland. Before he goes he wants to extend the hand of friendship to Enrico and ask for Lucia's hand in marriage. This frightens Lucia, who prefers to keep their love secret. Although Edgardo detests Enrico, who killed his father and stole his inheritance, he is prepared to put vengeance aside so he can be united with Lucia. The two affirm their love for each other.

Act II The Marriage Contract

Lucia De Lammermoor Aria

Lucia De Lammermoor

Scene 1 Enrico's apartments in Lammermoor Castle

Enrico nervously awaits the marriage that he has hastily arranged between Lucia and Lord Arturo Bucklaw, but is concerned that Lucia may oppose it. Normanno, however, has a plan: he has been intercepting Edgardo's letters and has forged one supposedly revealing that Edgardo has been unfaithful to Lucia. When Enrico shows her the letter, Lucia is distraught. Sounds of welcome are heard in the distance: it is Arturo arriving for his wedding to Lucia.

Raimondo tells Lucia that, although letters to her lover were intercepted, he has managed to have one of them safely delivered. He takes Edgardo's apparent failure to reply as proof of his infidelity, and forces Lucia to do her brother's bidding and marry Arturo. Install chase app.

Scene 2 The Great Hall of Lammermoor Castle

Wedding guests have assembled to welcome Lord Arturo Bucklaw. Enrico warns him not to be concerned by Lucia's sad demeanour, as she is still grieving for their mother. Lucia enters and is forced to sign the marriage contract. Edgardo unexpectedly arrives. He is challenged by Enrico and Arturo who demand that he leave, but Edgardo insists on his right to be present. When Raimondo produces the signed marriage contract, Edgardo denounces Lucia.

Interval of 20 minutes

Act III

Scene 1 A ruined tower Gpx viewer.

A fierce storm is raging. Edgardo is confronted by Enrico, who savagely torments him with the news that Lucia is in the marriage bed with her new husband. Both challenge each other to a duel at daybreak in the graveyard at Ravenswood.

Scene 2 The Great Hall of Lammermoor Castle

The celebration of the wedding guests is abruptly halted by Raimondo: he tells them that Arturo has been murdered by Lucia. When Lucia enters, she is clearly out of her mind. She plays out a fantasy of a wedding with Edgardo until, physically and emotionally exhausted, she collapses. Enrico is filled with remorse. Raimondo rounds on Normanno as the cause of this bloodshed.

Scene 3 The graveyard of the Ravenswoods

After Melba's reign as Lucia, Sembrich returned, often with Enrico Caruso as her Edgardo. The tenor hero was often cast with a heavier voice than it is today, with singers like Francesco Tamagno, Verdi's first Otello, and Francesco Vignas and Andreas Dippel, both Wagnerians, taking the part at the Met. One reason may have been that Lucia was often heavily cut, and would sometimes end after the mad scene, eliminating Edgardo's lyrical final scene. As a truncated Lucia made for a rather short evening, the program was sometimes supplemented by a performance of Cavalleria Rusticana or Pagliacci, or some other short piece. Giuseppe Cremonini, one of Melba's partners, sang both Edgardo and Turiddu in Cavalleria in the same evening. Edgardo's final scene was included in Caruso's performances, but it wasn't until Beniamino Gigli sang the role in the 1920s that the part was regularly attributed to a lyric tenor.

In 1911, the phenomenal Italian coloratura Luisa Tetrazzini made her Met debut as Lucia. Her career with the company was short, and she was succeeded in the role by noted sopranos Frieda Hempel in 1913 and Maria Barrientos in 1916. One of the most sensational singers of the century took over the part in 1921: the legendary Italian Amelita Galli-Curci (pictured above). Widely popular in part due to her best-selling records, Galli-Curci was particularly renowned for her remarkably beautiful vocal timbre. Musical America's critic wrote: 'Mme. Galli-Curci's lovely voice was of velvety sheen in the music of the unhappy bride and there was much winsomeness in her picturization of Donizetti's heroine. The ‘Mad Scene' has been sung more brilliantly, but not in recent memory have some of the earlier melodies come to the ear with such suave beauty of tone.'

Though she remained the most prominent Lucia through the 1920s, Galli-Curci sang less well as time went on, probably due to a thyroid goiter that eventually required surgery. In 1924, another Italian, Toti Dal Monte, made her Met debut as Lucia, and although she was highly regarded for the part in her native land, her success in New York was limited.

Then came, in 1931, the soprano who would dominate the role of Lucia for the next 25 years. French soprano Lily Pons (pictured above) was petite, pretty, and had an extraordinary upper register. She regularly interpolated Fs above high C, and even higher notes, into her performances. Though she was less of a virtuoso technician than her predecessors, she had plenty of charm, and audiences loved her. New York Times critic Olin Downes wrote, 'Miss Pons is not, and will not be, a Patti or a Tetrazzini. Her voice has range and freshness when it is heard at its full value, and not marred by faulty breath-support or vibrato. Certain passages yesterday were sung with marked tonal beauty and emotional color. In the ‘mad scene' some of the bravura passages were tossed off with a hint of the virtuoso spirit that this thinly glazed music demands. In other places the singer was not so fortunate.'

Pons's long reign in Lucia at the Met ended with a complete change in how the opera was viewed. Maria Callas (pictured above) sang only six performances of the part at the Met in 1956 and 1958, but her intense acting, musicality, and attention to text made for a powerful theatrical experience. No longer could Lucia be considered a bit of outdated fluff staged to show off the prima donna's virtuosity. The central figure had to be recognized as a tragic heroine of real emotional depth. Henderson's observations about the dramatic possibilities of the role were finally justified.

Taking Lucia seriously became the prevailing attitude of singers, conductors, and directors. It showed even when one more brilliant virtuoso, Joan Sutherland (pictured above and at the top of this page), made her Met debut in the part in 1961. Though she was by no means an actress in the mold of Callas, she had carefully worked on her portrayal with director Franco Zeffirelli in London. And not since the days of Melba and Sembrich had New York heard this kind of dazzling vocalism in Lucia. Critic Irving Kolodin said, 'Joan Sutherland came, sang, and conquered the Metropolitan Opera House in her awaited debut as Lucia … this is a voice consistent in timbre through two octaves (E flat to E flat in this part) with scarcely a break—full, ringing, and clear at the top, solid in the middle, viola-mellow at the bottom.'

Twenty years after her Met debut, Sutherland sang Lucia again in the company's first telecast of the opera. Approaching the age of 60, the Australian diva could still astound audiences, and along with the stylistically elegant Edgardo of Alfredo Kraus, the pair provided a glimpse of what gives Lucia di Lammermoor the popular appeal it has always enjoyed at the Met.

Peter Clark is the Met's Director of Archives

The action takes place in Scotland during the nineteenth century.

Act I The Parting

Scene 1 Ravenswood Castle

Enrico Ashton's family fortunes are in jeopardy. Only his sister Lucia can salvage the situation by means of an expedient marriage. Normanno reveals that Lucia is in love with Edgardo, laird of Ravenswood. The Ravenswoods were ousted by the Ashtons and their ancient estate is now in Enrico's possession. Edgardo lives on the edge of the estate in the ruins of a castle and has been seen having secret trysts with Lucia. Enrico vows to end the affair and destroy his enemy.

Scene 2

Accompanied by her companion Alisa, Lucia awaits Edgardo. She conjures up the image of a fountain where a jealous Ravenswood ancestor once killed his lover. She has recently seen the ghost of the murdered young woman, which Alisa interprets as an ill omen for Lucia's love affair with Edgardo. Lucia, however, dismisses her friend's warning.

Edgardo arrives and tells Lucia that he must soon leave for France in order to form an alliance to fight the cause of Scotland. Before he goes he wants to extend the hand of friendship to Enrico and ask for Lucia's hand in marriage. This frightens Lucia, who prefers to keep their love secret. Although Edgardo detests Enrico, who killed his father and stole his inheritance, he is prepared to put vengeance aside so he can be united with Lucia. The two affirm their love for each other.

Act II The Marriage Contract

Lucia De Lammermoor Aria

Lucia De Lammermoor

Scene 1 Enrico's apartments in Lammermoor Castle

Enrico nervously awaits the marriage that he has hastily arranged between Lucia and Lord Arturo Bucklaw, but is concerned that Lucia may oppose it. Normanno, however, has a plan: he has been intercepting Edgardo's letters and has forged one supposedly revealing that Edgardo has been unfaithful to Lucia. When Enrico shows her the letter, Lucia is distraught. Sounds of welcome are heard in the distance: it is Arturo arriving for his wedding to Lucia.

Raimondo tells Lucia that, although letters to her lover were intercepted, he has managed to have one of them safely delivered. He takes Edgardo's apparent failure to reply as proof of his infidelity, and forces Lucia to do her brother's bidding and marry Arturo. Install chase app.

Scene 2 The Great Hall of Lammermoor Castle

Wedding guests have assembled to welcome Lord Arturo Bucklaw. Enrico warns him not to be concerned by Lucia's sad demeanour, as she is still grieving for their mother. Lucia enters and is forced to sign the marriage contract. Edgardo unexpectedly arrives. He is challenged by Enrico and Arturo who demand that he leave, but Edgardo insists on his right to be present. When Raimondo produces the signed marriage contract, Edgardo denounces Lucia.

Interval of 20 minutes

Act III

Scene 1 A ruined tower Gpx viewer.

A fierce storm is raging. Edgardo is confronted by Enrico, who savagely torments him with the news that Lucia is in the marriage bed with her new husband. Both challenge each other to a duel at daybreak in the graveyard at Ravenswood.

Scene 2 The Great Hall of Lammermoor Castle

The celebration of the wedding guests is abruptly halted by Raimondo: he tells them that Arturo has been murdered by Lucia. When Lucia enters, she is clearly out of her mind. She plays out a fantasy of a wedding with Edgardo until, physically and emotionally exhausted, she collapses. Enrico is filled with remorse. Raimondo rounds on Normanno as the cause of this bloodshed.

Scene 3 The graveyard of the Ravenswoods

Among the tombs of his ancestors, Edgardo awaits Enrico's arrival. Believing that Lucia was unfaithful, he reflects on the emptiness of his life and how death would be a welcome release. Lammermoor retainers tell him that Lucia is close to death and is calling for him; before he can leave to be with her, Raimondo brings news that she has died. Wishing only to join her in death, Edgardo kills himself.